Digital Art & the Knight's Tour Problem

I became recently interested in the Knight’s Tour problem. It is one of the oldest problem in computer science, known for more than 1000 years! I have written a program in Scala that solves it for arbitrary-shaped chessboards. I find the visual patterns in the solutions quite interesting. In this article, I will talk about that.

The Background Story

The Knight’s Tour is a famous problem in computer science and chess. It consists in finding a sequence of moves of a knight on a chessboard, such that the knight visits every square only once. The tour is said to be “closed” if the starting position is reachable with a valid move from the ending position. The Knight’s Tour problem is an instance of the more general Hamiltonian path problem in graph theory, and the closed Knight’s Tour problem is an instance of the Hamiltonian cycle problem.

An open Knight’s Tour. Source: Wikipedia

The earliest known Knight’s Tour was described in an Arabic manuscript from al-Adli ar-Rumi, a professional chess player who lived in Baghdad in around 840 AD. It was then rediscovered much later in 18th century and several famous mathematicians such as Leonhard Euler have worked on it.

It is known that the Hamiltonian path and Hamiltonian cycle problems are NP-complete. A brute-force approach would be totally intractable: on a \(8 \times 8\) board there are approximately \(4*10^{51}\) possible move sequences! Interestingly, in the case of the Knight’s Tour, it is possible to find solutions in a linear time, thanks to useful heuristics. In 1823, H.C. von Warnsdorf1 described a heuristic to find a Knight’s Tour in linear time. The Warnsdorf’s rule can be described by recurrence as follows2:

Given that the Knight is placed on the nth square of the path, let the (n+1)th square of the path be the square which:

- is adjacent to the nth square (i.e., it can be reached with a single Knight’s move)

- is unvisited (i.e., it did not appear earlier in the path) and

- has the minimal number of adjacent, unvisited squares

The question that remains is how to handle ties between two or more unvisited squares. There was a bit of controversy about that. Warnsdorf claimed that no matter which random choices are made to break the ties, the path produced is always a tour, which turned out to be false2. There exists better ways to break the ties and more generally to find a tour, but I am not doing to go into details here.

In the next section, I am going to introduce the little software I wrote in Scala, which uses Warnsdorf’s rule with random tie breaking !

Solving the Knight’s Tour

The source code is available on GitHub here. Here is a little tutorial about how to use the program. The program is currently distributed as an SBT project. I would recommend you to clone the repository and to open the project in your favorite IDE (such as IntelliJ IDEA or Eclipse) and simply open a Scala worksheet.

First, let us import the classes ChessBoard and KnightTour from the chesstour package and define the path to a folder for our output.

import chesstour.{ChessBoard, KnightTour}

val output_folder = "knight/" // define an a path to an output folder

Let’s instantiate an \(8 \times 8 \) Chessboard and pass it to a new instance of KnightTour.

val board = new ChessBoard(8,8)

val knight = new KnightTour(board)

Now let’s find a closed tour using Warnsdorf’s heuritic !

val tour = knight.warnsdorfsHeuristic(closed=true)

This will produce a closed tour from a random starting position on this board. We can produce an output using the draw method:

tour.draw(path=folder)

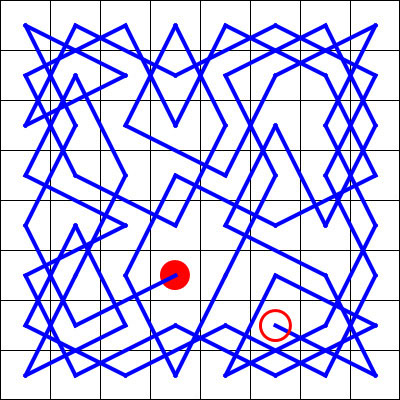

This will draw the tour and save it in a .png file, such as this one:

We can continue and find tours on boards with different dimensions. However, it is very unlikely to find twice the same tour, given that ties are solved randomly. For convenience, I provide a pair of functions to save and load a tour, so that you can use it later again:

tour.save(output_folder) // The tour is saved simply in a file <hashcode>

val t = ChessTour.load("knight/<hashcode>") // Load the tour from file

Note that a (closed) tour may be difficult or impossible to find depending on the dimensions of the board. It was showed that a tour exists for any board whose smaller dimension is at least 53 and that a closed tour exists if the number of square is even (i.e., \(m\) and \(n\) are not both odd). However, finding a tour becomes much more difficult when the size of the board grows2. The existence of a tour in non-rectangular boards is unknown a priori. We are going to talk a bit more about that in the next section!

The Knight’s Tour as Digital Art

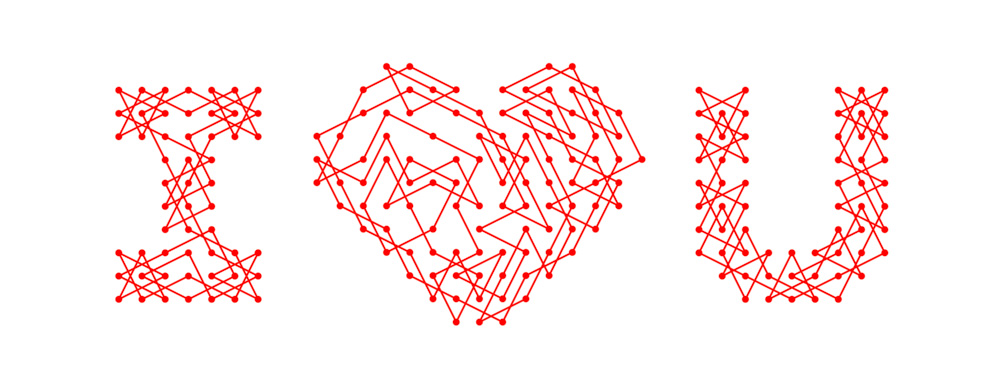

I find the random patterns created by the solutions of the Knight’s Tour really interesting. So I had the idea to let the algorithm run on boards with custom shapes. My first idea was to try on a board in the shape of an heart (yes, computer science can be romantic!). I took a basic drawing of an heart from the Internet that I reduced down to \( 30 \times 30\) pixels. This resulted in this image, if we look at it pixel-wise.

Using ChessBoard.fromMask, you can use this image as a mask to initialize a board:

val board = ChessBoard.fromMask("knight/<mymask>.png")

// val board = ChessBoard.fromMask("knight/<mymask>.png", switch=true)

By default, all the transparent or white pixels will be taken out from the board. If you set the switch parameter to true, you can use the same picture as negative.

The problem with arbitrary shapes is that it is rather unlikely (or even impossible) to find a (closed) tour. But that’s ok. With the argument closed=true you declare expressively that you are only interested in closed tours. The algorithm tries to return a cycle, no matter if all squares are visited. With the argument complete=true you additionally say that you want a complete tour, i.e. that all squares are visited once. This might not be possible, but the algorithm will perform a number of n attempts, after which it will return the tour found with the highest number of square visited.

val tour = knight.warnsdorfsHeuristic(closed=true, complete=true, n=1000)

The result might not be a closed tour on the custom board, but at least the largest cycle the algorithm could find using Warnsdorf’s heuristic and the given number of trials.

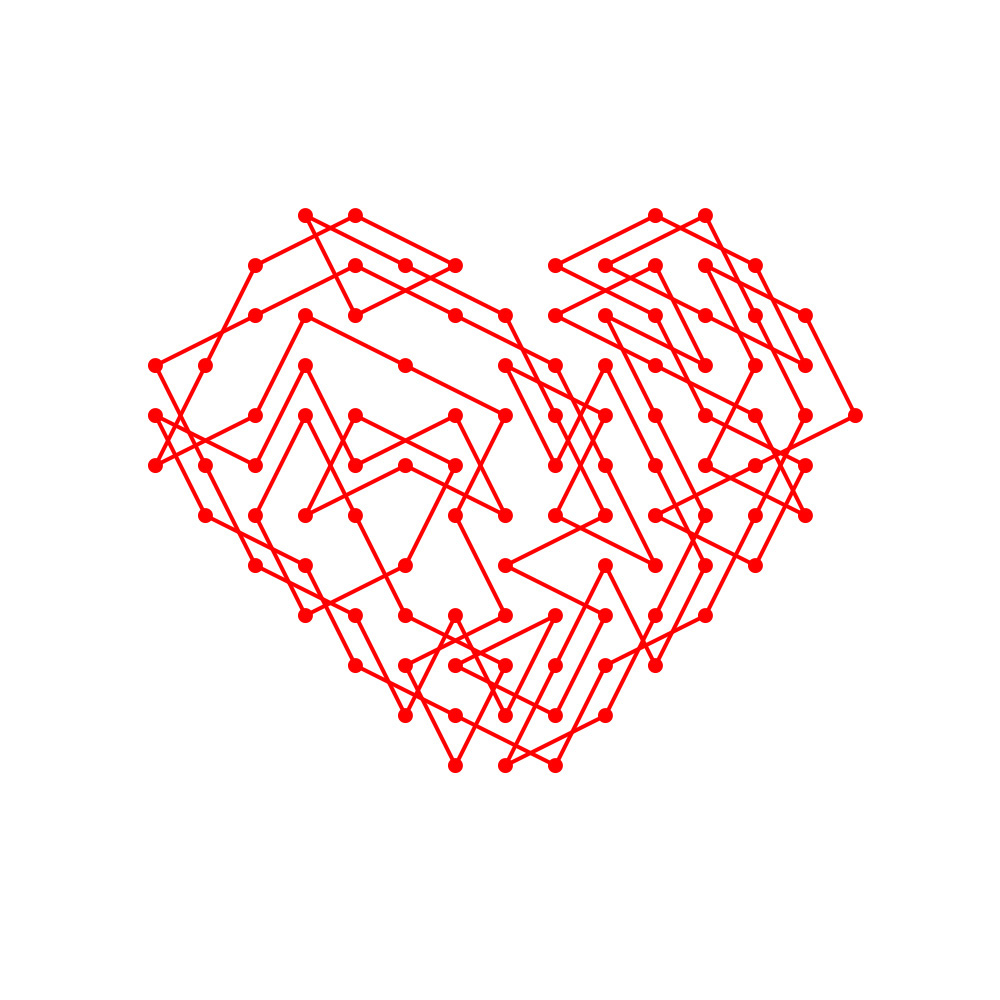

By running it several times, you always get different results, because the starting square changes at each attempt and the ties in the Warnsdorf’s rule are solved randomly. Each result is unique. Sometimes, it is surprising, ugly or good-looking. For example I like this one especially:

The method simulate gives you more control on the aspect of the output. You can change the size of cells cellSize, the size of the nails nailSize, the width of the line lineWidth, declare if the drawing should be closed (closed) as well as the color of the visualization (color):

tour.simulate(cellSize=50, nailSize=15, closed=true, path=output_folder)

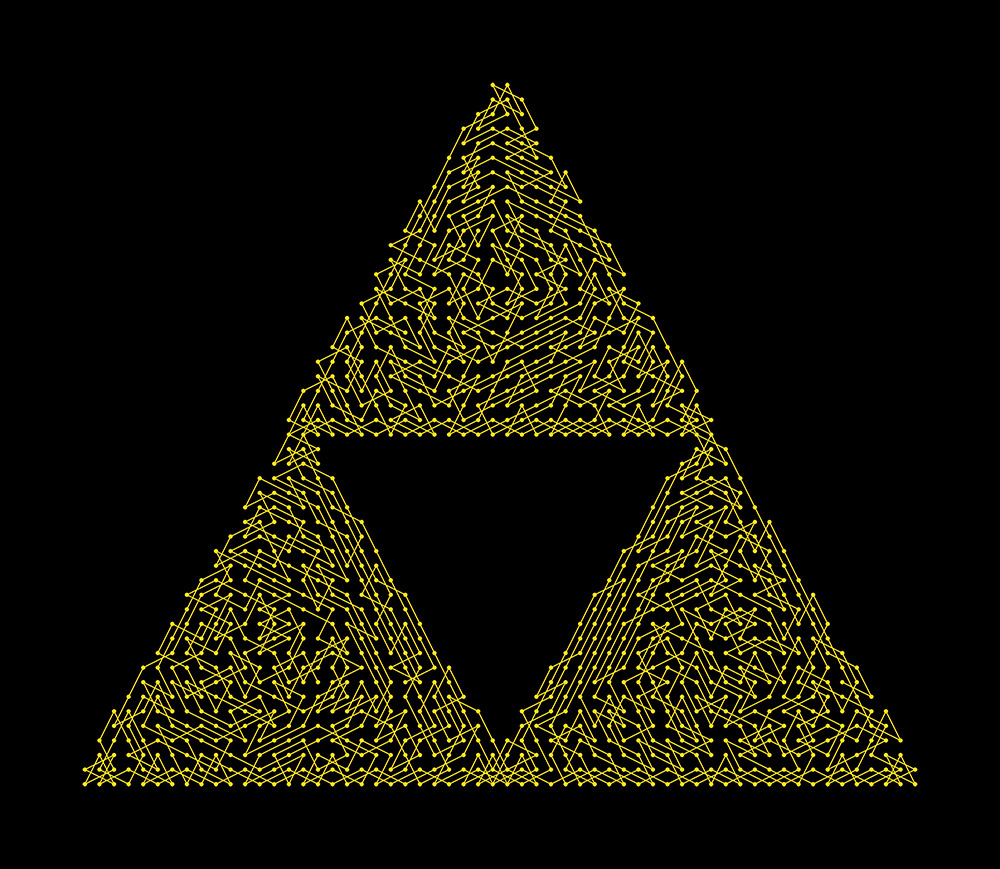

Here are a few example of designs I produced this way:

Do you like them? You can buy them on Redbubble here! My preferred one is this laptop skin.

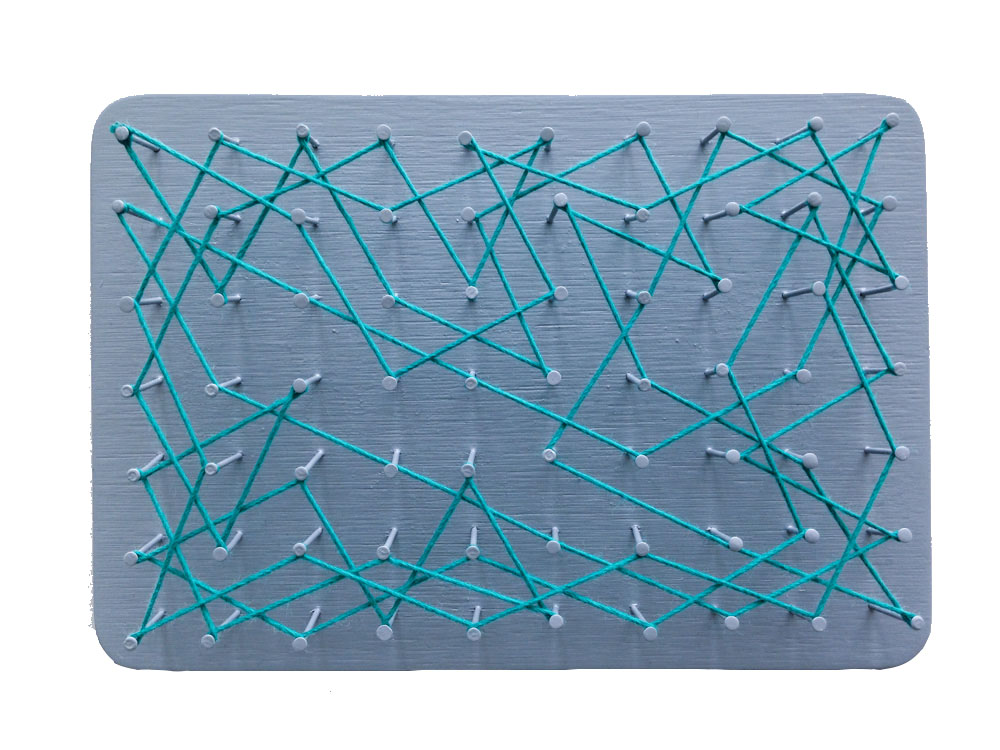

I am also going to make a real-world piece of art. I will take a board, nails and a string and represent the result of my choice. I have done a study for it already (on a small used cutting board) to see the real colors:

I am going to make one or two copies on boards of size greater than 1 meter. I will post the results here too!

Future Work

The current algorithm can be extended in several ways, such as:

- Supporting different heuristics45 and (better) tie breaking strategies2.

- Generalize the problem to other chess figures than the knight6.

For the first item, I might do it, because this will help getting more complete, or closed solutions. For the second one, I am not sure yet :)

More Resources

Aww. I see that you found this post interesting. Here is a list of selected resources about the Knight Tour problems that I found on the Internet:

- Knight’s Tour Notes by George Jelliss

- A nice video explaining of how to solve the Knight’s Tour by hand

- Warnsdorff.com and this GitHub repository from Douglas Squirrel

- A collection of implementations in 48 different programming languages.

By looking around for resources about the Knight’s Tour on the Internet, I found out that many have disappeared, because the pages were not maintained anymore. That’s a pity. I would instead encourage you to read the historical literature.

By the way, I’m not sure, is it Warnsdorf or Warnsdorff ? I found both writing in the literature and Internet.

Sources

-

Warnsdorf, H.C. (1823). Des Rösselsprunges einfachste und allgemeinste Lösung, Schmalkalden. ↩

-

Squirrel & Cull (1996). A Warnsdorff-rule algorithm for knight’s tours on square chessboards. Oregon State REU Program. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Cull, De Curtins (1978). Knight’s tour revisited. Fibonacci Quarterly. ↩

-

Parberry (1997). An efficient algorithm for the Knight’s tour problem. Discrete Applied Mathematics. ↩

-

Lin, Wei, (2005). Optimal algorithms for constructing knight’s tours on arbitrary n×m chessboards. Discrete Applied Mathematics. ↩

-

Chia, Ong (2005). Generalized knight’s tours on rectangular chessboards. Discrete Applied Mathematics. ↩